When I was 13 years old, my mother let me redecorate my bedroom.

It soon became awash in lilac and white hues, punctuated by white wicker furniture, as befitted the early 1980s. When it came to choosing artwork for the wall, I found the ideal black and white photograph of a couple leaning into each other near a bank of elevators. It was by Helmut Newton, called Woman into Man, and it was everything my teenage self so longed to be: sophisticated, worldly, knowing. The woman was all angles and suggestive pose, with the tuxedo-dressed man standing so closely that the cigarettes dangling from each subject’s lips touch. It took several decades for me to realise that the man in the photo was, in fact, another female. It amused me to think of such erotica on the walls of my family home. I wonder now if my mother had thought anything about it.

Helmut Newton, Woman into man, Paris, 1979, copyright Helmut Newton Estate, courtesy Helmut Newton Foundation

After university, straddling the work worlds of both magazines and film, I was drawn to Newton’s photos once more. The women were always spectacularly beautiful: high cheekbones, long limbs, pert breasts and full lips at a time when Kardashianesque injectables were decades away from touching any models’ mouths. In the 1980s in Movieland, I had learned that an actress’ main currency was to be ornamental. But Helmut’s women were not decorative. In his photo of actress Sigourney Weaver, for instance, she is statuesque and powerful, with not even the tiniest smile dancing across her lips. She isn’t there to seduce the man behind the lens. There is no come-hither look. It is a ‘come, if you dare’ stare, but you don’t really know what she is thinking. That is entirely the point.

Newton’s works have mystery, glamour and not a little subversive edge. As I entered my twenties, I would study his images for the world of possibility that they held: it was not only evident in the scenes they showed, but in the portrayal of a universe in which women were demanding, sexual, submissive, playful, delighted and sometimes angry. These women were nuanced, and they did not have to give up their femininity to be so.

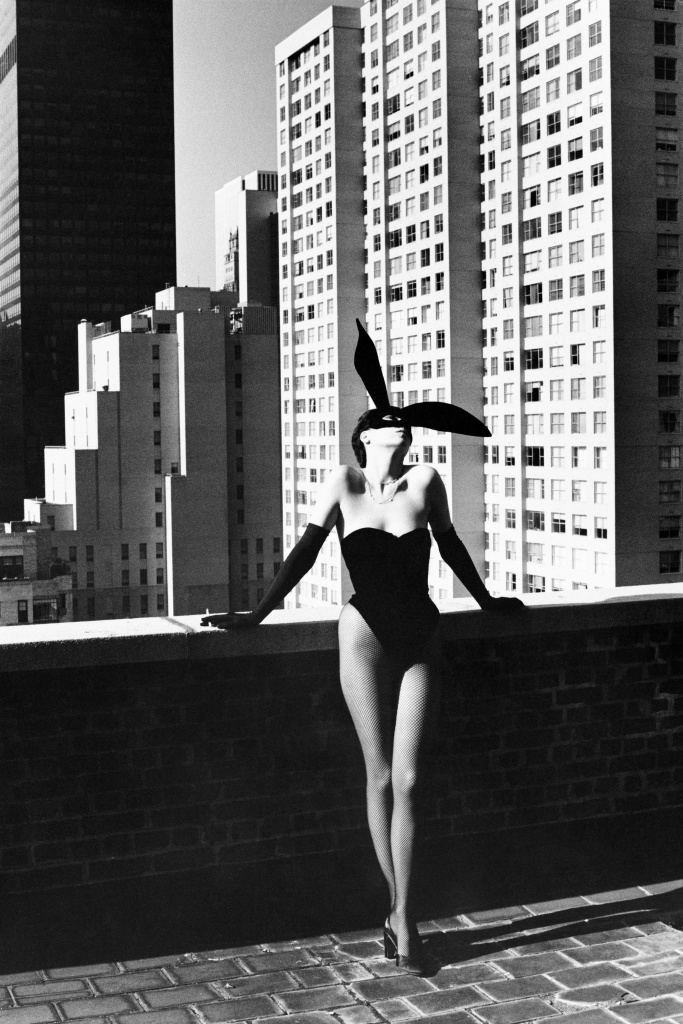

By the time I entered the ’90s, I was living in New York. When I stumbled upon one particular Helmut Newton image, it fascinated me: taken in 1975, it was of then-model Elsa Peretti, standing against the edge of a rooftop, the tall buildings of New York behind her. She is dressed in a manner both unlikely and completely understandable in Manhattan, depending on which downtown haunts you frequent: she wears a strapless corset, fishnet stockings and Playboy Bunny-style ears. I found it outstandingly beautiful, but I was also aware of the subtle themes in the shot. She was alone. She wasn’t waiting for anyone. She seemed to be wearing the costume for herself, and if desire is in that photo, it is hers alone.

Helmut Newton, Elsa Peretti, New York, 1975, copyright Helmut Newton Estate, courtesy Helmut Newton Foundation

Newton showed me another world of possibility, and that was entirely away from his negatives and film. Here was a man who had fled Europe and made a life in my own hometown, Melbourne. Like me, he had the dark shadows of the Holocaust hanging over his head – although I was a generation removed. Like me, he was Jewish. And, like me, he had wanted to operate in the world in an expansive way, making a name for himself globally and remaining current and relevant until his death. He showed me that, that might be possible, even if you come from a background where everything had been lost, and even if you once made your home in the smallest speck of a city, as compared to the world’s stage.

More recently, I wondered if Newton’s work would still feel relevant to me. Would my feminist side kick in, and would I rail against the breasts, the milky thighs, the sometimes-tied-up women? When I inspected the work of Helmut Newton on the walls of the Jewish Museum of Australia, I saw many things. Beauty. Artistry. Controversy. I saw that he was so ahead of his time in so many ways, often gravitating towards both men (David Bowie, for example) and women with an androgynous look. There is no judgement in his photos that depict sexuality, merely fluidity. And as posed as some of the models are, there is no contrivance. They are clearly not snapshots from real life, set up as they are with carefully choreographed arms and legs in some cases, but they seem real because of the expressions on the subjects’ faces, the invisible trust that hangs in the air. Like Helmut Newton, they are not one thing. They evolve, they interest, they question. They hold complexity and depth. They are all compelling, but some are disturbing, like the woman who stands naked in a hotel room, her only accoutrements being a neck brace, thigh-to-toe leg bandage and cane. Even she looks anything but a victim. She is defiant, and not to be pitied. Newton once said: “In my pictures, the woman is completely in charge—she’s the mistress of the situation. My women are like ice; they can take care of themselves.”

I think that’s the message I always liked. In Newton’s world, it seems, strength matters far more than beauty. I’m sure that’s what I saw, when I put his print up on my wall all those years ago.

Rachelle Unreich has been working as a journalist for 35 years. Her writing appears frequently in The Age and Sydney Morning Herald newspapers, and she has contributed extensively to publications in the US, UK and South-East Asia. She is based in Melbourne.

This essay was originally published in Issue #1 of ILLUMINATE.